If ever you were searching for a way to convince someone under 25 to save some of their money, the phrase on which you may be inclined to lean the most heavily would undoubtedly be compound returns.

Compounding is the mantra of long-term investors, and for good reason: compounding returns are a significant part of how long-term investing accumulates a substantial chunk of gains. But you don’t have to be under 25 to benefit from compounding returns; any investor seeking to accumulate long-term gains benefits from compounding. In fact, compounding is a critical part of FIRE, so let’s talk about it below, including how to make the most of it.

Let’s start with the basic concept of “principal,” which is the money that you invest. If you take $1,000 from your paycheck and invest it in some sort of account or asset, then your principal is $1,000. Compounding means that, as the years go by, your returns are earned not just on your principal, but also on any money that has previously been earned on your principal. An example does the most justice.

The simplest form of compounding is compound interest, and it goes like this. If you take that $1,000 and put it in a savings account that earns 10% per year (not a real life example…), at the end of the first year, your account will have a balance of $1,100. In the second year, the 10% interest earned is calculated not only on your original $1,000 principal, but also on the $100 you earned in the first year. So in year 2, you earn 10% on the $1,100 balance that you had after year 1. At the end of year 2, your new balance is $1,210. At the end of year 3, your new balance is $1,331. You see that the amount you earn actually grows ($100 in year 1, $110 in year 2, $121 in year 3) even though you didn’t make any deposits.

Compare compounding interest to “simple” interest. Simple interest means that the interest earned each year is calculated only on the principal. In the above example, this means that (assuming you make no deposits or withdrawals), in each year you’d earn $100, calculated as 10% of your principal, $1,000.

The benefits of compounding interest might not seem readily apparent at first – the difference after two years between compound and simple interest in the above example is a paltry $10: $1,200 in the simple interest account vs. $1,210 in the compound interest account. But, rest assured, compounding returns are like those cartoons where the character creates an avalanche starting with a tiny snowball. At first the gains are incremental, but once they get roaring, they multiply exponentially. In fact, with compounding returns, it doesn’t take long for the majority of the returns to be accumulating on returns themselves rather than the principal.

Let’s dig further into the example above. But first, I’d point out that there are a number of compound return calculators on the internet you can use to calculate these returns for yourself using numbers of your choice. The one I use most often is here:

https://www.investor.gov/financial-tools-calculators/calculators/compound-interest-calculator.

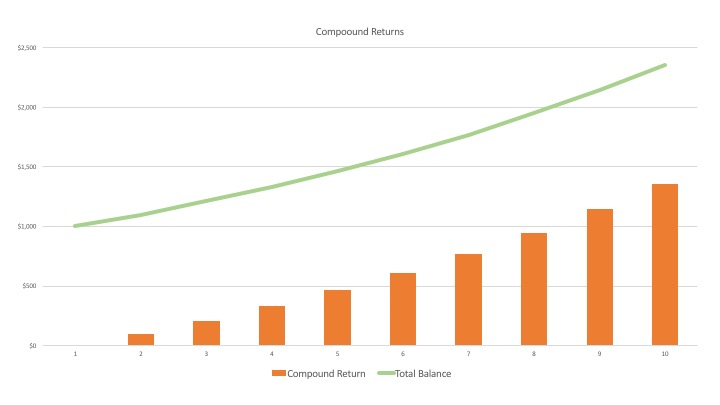

But for now, here’s a chart that further illustrates the concept of compounding, expanding on the example above:

| Year | Interest Earned | End Balance |

| 1 | $100 | $1,100 |

| 2 | $110 | $1,210 |

| 3 | $121 | $1,331 |

| 4 | $133 | $1,464 |

| 5 | $146 | $1,611 |

| 6 | $161 | $1,772 |

| 7 | $177 | $1,949 |

| 8 | $195 | $2,144 |

| 9 | $214 | $2,358 |

| 10 | $236 | $2,594 |

| 11 | $259 | $2,853 |

| 12 | $285 | $3,138 |

| 13 | $314 | $3,452 |

| 14 | $345 | $3,797 |

Look how quickly the returns start to accumulate once they get going. By year 9, the total interest earned, $214, means that greater returns are being earned on the previously accrued returns than the principal itself. If you keep going with this chart, the returns continue to grow. By year 40, your ending account balance would be $45,259.

Keep in mind that for the same reason compounding is beneficial to investors, it can cause some serious damage when it comes to debts. Now, not all loans require repayment on a compound basis – some are only calculated on a simple basis. But, for those that are compounding, if you don’t at least pay off the newly accumulated interest each period, the amount of the debt will compound and grow exponentially. That out of the way, let’s go back to the good side of compounding.

The above example is a little unrealistic, as you might suspect, because it involves continually accruing cash returns; i.e., interest payments paid out to you, increasing your cash balance. The reason this is unrealistic, as you might suspect, is that there are no savings accounts in the world that pay this much interest. The above example also doesn’t take into account deposits that you make into the account.

The good news is that the concept of compounding does translate to stock market investing, albeit a little less directly. In prior posts, I discuss that I assume an average annual rate of return of 6%. This is, in effect, a compounding rate of return because I assume that the growth in market value of the total investment portfolio grows 6% each year, calculated on top of each year’s prior ending value. As I’ve discussed previously, nobody should expect 6% of linear growth – reality is not so clean; rather, the assumption is that, after 20 or 30 years, looking back, you’ll see that the portfolio grew on average about 6% per year, accounting for the fact that in some years it grew more and in others by less (or even declined).

Assuming that the stock market provides compound returns is not unreasonable, particularly because when you read about growth of a particular index over the year, it’s measured against an ending value of the prior year. That’s essentially what compounding is – calculating returns based on the total value rather than an initial value (such as the principal).

In the context of the stock market, “returns” might be a bit of a misnomer when talking about market value. Again, an example is the best way to explain it. If you purchase a share of stock at $100 and it grows 10% in year 1, at the end of the year, its market value is $110. If it grows another 10% in year 2, at the end of year 2, the share’s market value would be $121. Still tracks the savings account, right? Except that $121 is not cash – it’s actually market value. The first difference is that you have to sell the stock before realizing the returns (and of course pay tax on the capital gain).

The other difference is that unlike your savings account, the market value of a share of stock – or indeed, your entire market-invested portfolio – can decrease. This non-linearity means that the “compounding” aspect of stock market gains is a little different than compound interest to the extent that it’s not always growing. Nevertheless, these differences aside, the same concept applies. When evaluating year over year returns, the return is calculated on the prior year’s closing market value, and not the value of your principal – meaning that when projecting anticipated future returns, each year’s return builds on the prior year’s. What this boils down to is that as your account balance grows, the returns themselves also grow – which is exactly why compounding is beneficial.

Even though an increasing market value is not exactly the same as compounding interest, there are some aspects of stock market investing that do more precisely mirror the example of compounding interest shown above. The first is if you reinvest dividends. Each time you reinvest a dividend, you gain more shares of the stock that paid you the dividend. Not only do you then own more shares that can benefit from an increase in market value, but you’ll also receive future dividends from the totality of shares you own – including those you acquired by reinvesting previous dividends. In this sense, you earn more from dividends over the years as a result of receiving previous dividends – which is just like the compound interest example above.

Mutual funds and ETFs bake in the concept of compounding by automatically reinvesting distributions as additional shares of the fund. Over the years, the number of shares you own of the mutual fund or ETF will grow without you doing anything. Each time there’s a subsequent distribution, you’ll receive those distributions based on a continually growing number of shares of the fund that you own.

The second aspect of market investing that resembles compound interest is bonds. The best way to make this comparison is with an example. If you purchase a bond with $1,000 that has a 10% interest rate and a one year maturity date, at the end of the first year, you’ll have $1,100. If you take that $1,100 and buy a new bond with the same 10% interest rate and one-year maturity, at the end of year 2, you’ll have $1,210. You see how this matches the chart above. The concept is the same as compound interest – each year you reinvest your gains, and then future gains accrue on an amount that includes both your principal and your accumulated earnings to date, which in turn generates greater earnings. Just another form of compounding.

Compounding for FIRE Investors

The concept of compounding returns is vital to the FIRE investor for several reasons. First, and foremost, it underscores the advantage you gain by starting early. This is true whether you’re saving for early retirement, late retirement, or whatever – the longer you have the better. If you start younger you can invest less money and the power of compounding returns will get you to the same place as someone who starts later and invests more.

Second, compounding gives you a concrete reason to avoid the temptation either to skip an investment or withdraw money from your investment account. As should hopefully be clear from the discussion above, if you skip making one of your periodic deposits to your investment account or you withdraw money, you don’t just lose out on the face value of the amount of the missed investment or withdrawal – you also lose out on the future compounding returns. Keep this in mind when assessing the value of in the moment spending against long-term gains.

Third, compounding demonstrates how retiring early is sustainable. Once you’re retired and no longer contributing new principal (or contributing less principal), it’s still the case that your returns accrue against your accumulated value, plus what you continue to reinvest from interest payments, dividend reinvestment, etc. Even if you’re no longer depositing new principal, your continuing returns should, if you calculate reasonably correctly, sustain you for as long as you need.

Finally, compounding demonstrates how your average workaday investor can actually achieve early retirement (or retirement generally). If you’re thinking about starting, the figures can seem pretty daunting. Have you ever read one of the websites on FIRE – or even an article on a national news site – and seen figures like $2 million or $5 million or something that just seems absurd? Of course those articles are mostly intended for shock value, though as we learn when considering FIRE in greater depth, there’s some truth in them. If you want to retire at 40 or 45 and maintain a certain standard of living, you do need a decent amount of money, and some of these “shock” figures may not be inaccurate.

If you’re 30 years old and have $20,000 in the bank, getting to these numbers can seem quite the uphill climb. And it does take dedication and sacrifice to invest enough principal to generate decent returns. But, as compounding shows us, as we start to generate returns, the returns themselves actually increase, just like that cartoon avalanche. If you really boil down the numbers, and account for the potential to obtain compounding returns, you may see that you might actually be able to make early retirement happen. It’s always going to take some work – much like anything that’s worth achieving – but if it’s something you value, compounding can make those target numbers a little less daunting.