It’s only natural, after starting to invest, to become interested in the alternatives or variants out there. After you’ve taken that big leap from stashing money in a savings account to investing it in the stock market, you may start to feel like it wasn’t as big of a leap as you once thought it was. And with that comes curiosity about all the other investments that you may still be missing out on simply because they seem too complicated.

Let me state, before I continue, that in my opinion, buy and hold is the safest and perhaps most likely way to achieve an investment goal like FIRE. If the entire history of the stock market has shown us anything, it’s that over time it trends upward. While there may be some blips along the way, if you hold steady, don’t panic, and invest wisely, you’re likely to see returns down the road. That is, if history continues to repeat itself.

The reason I talk about these alternatives is that some people may have more appetite for risk and want to explore something new. For most long-term investors with day jobs, however, this discussion serves more to address a topic that may be bouncing around and perhaps dispel the notion that it’s a viable alternative to the buy and hold strategy.

With that, let’s talk about short selling, or shorting. This is one of the more common “alternative” methods of investing that you’ll hear about every now and again. You’ve probably also seen it in movies, like if you’ve seen The Big Short. That movie was actually about an even more complex form of short selling than I’ll talk about in this post, but the underlying concept is the same – investing on the basis that the asset prices will decline.

Short selling is one of those things you hear about in the context of investors making money even when the market is going down. And taking a “short” position frequently means exactly that – you enter a transaction in which you intend to profit from the price of a stock declining. This is in contrast to a “long” position, in which you purchase a stock with the goal of making money from the stock price going up. The buy and hold strategy is essentially that – taking “long” positions on stocks. (There’s more nuance to these definitions that I won’t get into here – but what I’ve stated is relevant for this post).

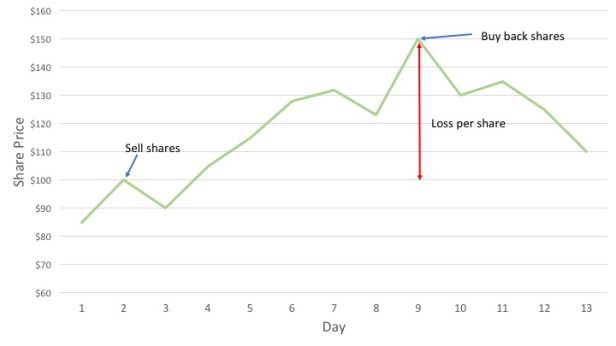

So how exactly do you profit from a stock going down in the short term? The general form of short selling goes like this. You find a stock – stock 123 – that you think will decline in the next week. To carry out the transaction, you “borrow” shares of 123 from an investor who actually owns the stock, and promise to return the shares within a specified window of time. This all takes place through a contractual agreement. Assume that you have to return the shares in 7 days.

Say that when you “borrow” the shares, they’re trading at $100 and you’ve borrowed 500 shares. You immediately sell those shares and pocket $50,000. By day 7, the share price has declined to $50 per share. On day 7, you buy back 500 shares for $25,000 and return those shares to their rightful owner. In this transaction, you’ve earned $25,000 (less the fee you paid to borrow the shares).

This is, in a nutshell, how you short stock. The timeline may be longer or shorter, but this is the basic concept showing how investors make money even when the price of a stock declines.

Short selling is not only done by individual investors – it’s also a tool that money managers might use to protect against market downside risk. The mechanics of this are more complex but follow the same basic structure – the idea is that if the market does go down, there’s a backstop so that the investor does not face the full repercussions of the fall.

Like anything else with investing, describing it on paper makes it seem easy so let’s talk about the risk. And that is, contrary to every other risk you might be familiar with in the stock market – that the stock actually goes up in value. While normally that’s a good thing, when you’re shorting a stock, an increase in value is actually the last thing you want.

Remember that if you’re shorting a stock, you’re contractually obligated to return the shares you borrowed, regardless of prevailing market price. So if, in the example above, 123 goes up to $150 on day 7, you still have to return 500 shares. This means you’ll have to buy them back to return them, and now that’ll cost you $75,000. When the price goes up, you lose $25,000.

And one thing about short selling is that, in theory, your risk is unlimited. Let’s explain.

When you buy a share of stock and take a long position hoping it will go up in the future, the most you can possibly lose is the money you spent to buy the share. So if you spend $10,000 to buy 1,000 shares of stock 234, and company 234 is wiped out, you lose $10,000.

But, in theory, the price of a share can rise infinitely. So, going back to shorting 123, there’s no cap on how much you can lose because of your contractual obligation to return those 500 shares on day 7. If the stock goes to $200 or $300 or $5,000 per share, you still have to buy 500 shares on day 7 to return them to the broker who loaned them to you. There’s essentially no limit on how much you can lose. And guess what, if you don’t return those 500 shares on day 7, the broker is going to sue you for them and your excuse that the price went too high won’t do you much good. Remember, the broker is losing money if you don’t return those shares – and will recoup that money from you.

In practice, most stocks don’t shoot up like this, but it’s not impossible – especially if you’re shorting penny stocks and the like. The lesson is – shorting can come with rewards but certainly carries some risks.

What about for FIRE investors? Your average FIRE investor is likely not shorting stocks, especially if pursuing a buy and hold strategy. Shorting is generally for risk-tolerant investors taking advantage of short swings and the market’s temporary backslides. If you’re hoping to retire in 10 or 15 years, trying to extract some additional value through short sales is risky, especially if you don’t know what you’re doing.

Think about timing the market. For your average investor, it’s difficult to track and predict when the market is going to swing one way or the other. At least with long-term investing, history has shown us that it tends to accumulate value, regardless of short-term volatility. However, to short a stock, you need to be precise with your prediction about when a particular share price is going to decline. Unless you’re able to do and understand the research, and, as much as I hate to say it – get lucky every now and again – shorting is a risky proposition.

Now that you have the context, make wise choices. If FIRE is your goal, give some serious, reasoned thought before you engage in risky endeavors like shorting stocks.