In a previous post, I discussed different methods of buying and selling shares: market and limit orders. In this post, I’ll discuss the stop loss – a related concept that pertains mostly to selling shares when they’re on the decline. However, as I’ll discuss below, stop losses aren’t only for losing stocks; they can also help to capture gain.

In this post, I’m generally only discussing stop losses for investors who take “long” positions; that is, buying shares with the intention of waiting for them to go up in price. Stop losses are also common in short-selling, but because most FIRE investors are not shorting stocks, I won’t get into the mechanics of those here.

Stop Orders

In its simplest form, a stop order (also known as a “stop loss”) is an order to sell a stock when it hits a certain price. The order doesn’t execute unless the stock actually makes it to that price, meaning that it stays open until it executes, expires, or you cancel it.

An example, you say? You’ve just bought 100 shares of XYZ for $50 each. You’re not sure where XYZ is headed, but you want to minimize the potential for downside risk, so you set a stop order at $40. This means that if the price of XYZ goes down to $40, the order will execute and you’ll “stop out” of XYZ at $40 per share, leaving you with a loss of $1,000. The idea is that selling at $40 prevented you from losing more if the stock continued to decline. Of course, as I’ve discussed before, you only actually lose money when you sell a stock, so keep in mind that a stop order ensures that you realize a loss at the specified price.

A bit more about the mechanics of a stop order. The “price” is the prevailing market price. So, in the example above, the order won’t execute just because there’s a bid in the market at $40. Rather, the order will only execute when the prevailing price – that is, the one you see when you check the stock price on your stock app or online – hits the specified price. At that point, the stop order becomes a market order and executes at the next available price. This means that you have to exercise the same caution you would with a general market order, such as with illiquid stocks or after-hours trading. Generally, if you place a stop on a liquid stock trading on a major exchange, the stop order will execute fairly close to the market price.

Most brokers also give you the option to set a “stop-limit” order, which is a stop order that becomes a limit order if the price hits the specified amount. The stop order becomes a limit order at that price, and the order only executes if it can be filled precisely at the amount you set. This means that the shares won’t sell unless there is a willing buyer at the exact price.

You can also place a stop order to buy shares when they hit a certain price. I discussed this concept in the context of limit orders. One difference between a stop order and a limit order to buy is that the limit order will fill at your specified price, while the stop order will generally become a market order unless you set a stop-limit order. The stop order therefore makes it more likely that your order will fill, while the limit order, if it fills, will only do so at the price you specify.

Another difference is that if you set a regular limit order, your bid price will be visible and available to the market before the trigger price is reached. A stop order won’t be available to the market until the trigger price is reached. So if you set the stop price to buy at $80, a seller currently asking $80.01 won’t see your potential order, whereas if you have a limit order at $80, that seller could see your bid and, if they want, could lower their ask to $80 so that the order would fill.

Capturing Gains and Trailing Stop Losses

There are several permutations of the stop order that make it more useful than simply getting you in or out of holding a particular stock. These scenarios apply when you want to capture a certain amount of gains.

Say you buy XYZ at $50 per share, and XYZ thereafter goes up to $60 per share. When it hits $60, you might decide to go into your portfolio and set a stop order at, say $58 per share. This way, you can continue to see if XYZ will go up, but, if it starts to decline, your shares will sell at $58, locking you in a gain of $8 per share. This gives you the potential for greater upside, but ensures that you make a profit on the stock.

If you’re using a stop order to capture gains, there’s a slightly more sophisticated version available for this, called a trailing stop loss. A trailing stop loss is a way to take advantage of a stop order that captures gains, but with the added advantage that you don’t really have to watch it. When you set a trailing stop loss, you set a percentage or dollar amount below the market price at which you want the stop order to execute. If the stock declines by that amount, the stop order will execute.

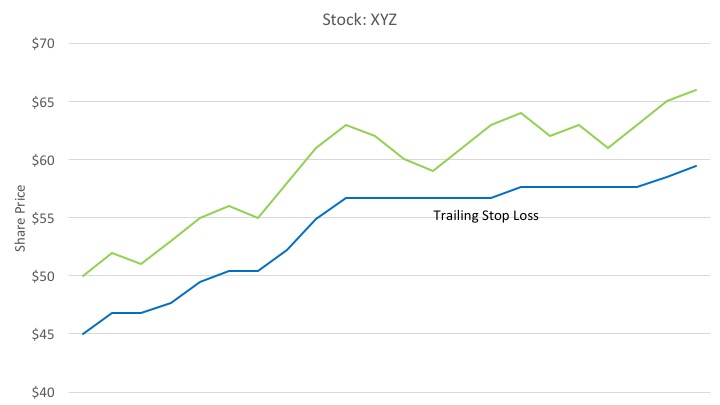

Back to XYZ. You’ve purchased at $50 per share, and set a trailing stop loss at 10%. As XYZ climbs, the stop loss follows XYZ up, allowing XYZ to go up in price.

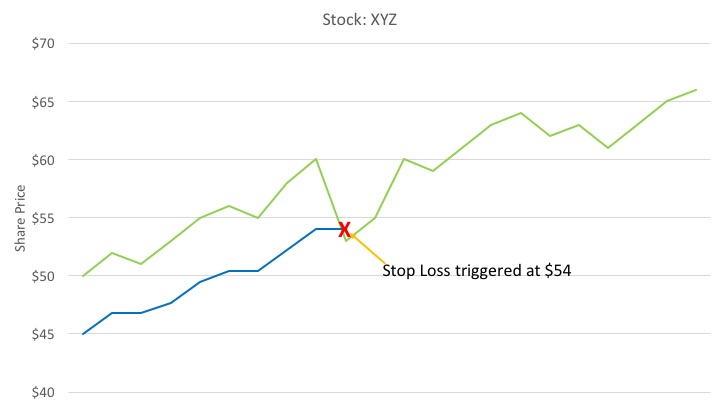

If, at any point, XYZ declines 10% from a price that it hits, the order will execute. So, if XYZ peaks at $60, but then has a bad day and drops 10% to $54, the stop order will execute.

Had XYZ made it to $70, the stop would be set at $63. Had XYZ made it to $80, the stop would be at $72. So you see, as the stock goes up, the stop loss point keeps going with it. Once the stock goes up, so does the floor. If XYZ makes it to $80 and that’s it, the floor stays at $72. That means, if it hits $80 and then hovers in the high-70s for 2 years, never going above $80 but never declining to $72, the stop won’t execute, and you’ll keep your shares. A trailing stop loss never moves down – it only moves up (unless you’re shorting a stock, in which case you can set the stop loss to move the other way).

The advantage is that a trailing stop helps you capture gain tied to the highest market price the stock reaches. If it starts to fall beyond your pre-defined threshold, the stop loss executes and you capture a certain amount of gain.

Setting a Trailing Stop

One thing that must be considered when setting a trailing stop loss is finding the right threshold to set it. It might not seem obvious at first, but if the trailing stop loss is too narrow, your order might execute simply due to daily market fluctuations rather than an actual sustained decline.

For example, if you set your trailing stop loss at 2%, that means that a fairly small dip might trigger it. If XYZ makes it up to $80, the stop loss will set at $78.40. Take a look at any major stock and you’ll see that it can swing within bands like this in relatively short periods of time. On a given day or week, XYZ might dip down a dollar or two, even if it’s generally still poised to rise. The risk is if XYZ hits $80, then the next day drops down to $78.40 in the course of a normal swing (maybe the market as a whole is having a bad day), your trailing stop loss executes and you’ve sold off all your shares of XYZ.

But, in the following days, it swings back up, recovering to $80 and then heading higher. That’s additional gain you’ll miss out on because your trailing stop loss was too narrow.

Finding the right place is a difficult balance. On the one hand, you don’t want it so far below that you lose all your gain if the stock declines. Setting one at 20 or 30% might negate the point of having a trailing stop loss in the first place.

However, you also don’t want it so close that it executes due to normal fluctuation of the daily market. There’s no magic number – setting one at the right amount takes experience. Generally, you’d want to know what the typical daily/weekly swing range is for the share and set it outside that range. If XYZ historically has swings of 3-5% in a given day or week, then you’d want to set a trailing stop loss at greater than 5% so that it doesn’t execute due to an ordinary fluctuation.

Market and Limit Orders

Trailing stop losses can also be set as both market and limit orders. Each has its risks. If your trailing stop loss becomes a market order when it executes, then it won’t necessarily execute at the exact price at which you set the stop loss. However, the trade will execute, even with the potential for variability in the price. So, if XYZ hits $72, the trailing stop will become a market order to sell at $72. If you have 100 shares, this could mean that 50 sell at $72 and 50 sell at $71.98, or something similar. If it’s a highly liquid stock on a large exchange, it will probably execute close to the price, but if it’s less liquid or the trailing stop loss is triggered during a period of high volatility, there may be a more significant difference in the final price.

If your trailing stop loss becomes a limit order at the stop loss price, it adds some certainty to the price at which it executes. However, if the order cannot be filled at the price you set, it won’t execute, leaving an open limit order in place until the exchange can find a willing buyer. If your trailing stop loss to sell 100 shares of XYZ becomes a limit order at $72, but a buyer can only be found right at $72 for 50 shares, the order will fill for those 50 shares at $72, but the remaining 50 shares will remain yours for the time being, subject to further whims of the market.

Trailing Stop Losses when Purchasing

The above discussion assumes that you purchase stock and then add the trailing stop loss later. But, you can also add a trailing stop loss at the same time you make the initial purchase. If the stock goes up, the trailing stop loss works just as described above; however, if the stock never goes up after you buy it, the trailing stop works just like a regular stop loss.

Assume you purchase XYZ at $50 and set a trailing stop loss with a 10% window. After you buy, XYZ just starts to go down. At this point, your stop loss is at $45. If XYZ fails to ascend and ends up just sputtering down to $45, the stop loss is triggered and will convert to a market or limit order depending on how you set it.

The point of this example is to show you that a trailing stop loss does not operate only when a stock gains, but can also execute when your position is at a loss. For example, if XYZ moves up to $52, the stop loss comes up to $46.80. But if then XYZ declines and hits $46.80, the stop loss executes and you take a loss even though there was some initial gain. A trailing stop loss doesn’t wait for you to get to the point where it’ll only execute when you’re up – it can execute when you’re down too. The point is that you have to consider when to set a trailing stop loss, and understand that if the stock doesn’t rise, the trailing stop loss might execute when you’re down.

Stop Losses for the FIRE Investor

Stop losses are more commonly used by active traders than investors pursuing a long-term buy and hold strategy. If you have time on your side for stocks to recover, the thought might go that there’s no need to stop the bleeding on a losing stock when it could recover over time. Or, if you decide it’s best to sell a stock that’s down in the interest of loss harvesting or simply to re-allocate your money to something else, you generally won’t need an automatic order open to do it for you. Rather, if you rarely sell shares – at least before you’re retired – you can determine whether or when to sell a share by monitoring your portfolio and making the decision as you’re reviewing it.

The same is true of trailing stop losses on a stock you buy for long-term growth. If your goal is appreciation over time, you don’t want to sell off the stock just because it shows some short-term gains. Trailing stop losses – when used for stocks that are going up in value – help you “capture” gains before the stock settles back down. But, like with stop losses generally, with time on your side, the goal is to see the stock continue to rise, notwithstanding what may be a downward blip. Remember too that selling a share will result in capital gains taxes. If you don’t immediately need the proceeds of a sale to live off, you may be forcing yourself to incur taxes before it’s necessary.

So while stop losses can be a useful tool, they may not be necessary for a FIRE investor pursuing a buy and hold strategy. If you decide to trade more actively, however, stop losses are a valuable way to help mitigate losses and capture gains.