Remember how I said that a 6% return is long-term? Because I said it again, here and here.

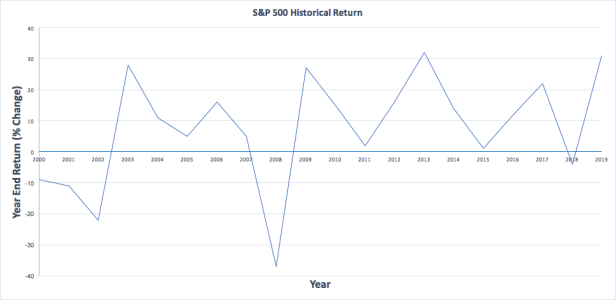

If you’re reading this in 2022 or at some point in the future that resembles early 2020 or seemingly the entirety of 2022, now might be a good time to remember exactly what I meant in those earlier posts. The point I was making is that the market does not move in linear fashion – meaning that your portfolio will not increase by a clean 6% in value each year. Rather, as we’re being forced to recall, there are years when the market value of your portfolio will increase far more than 6% and there are years when it will, in the loudest way possible, decrease.

It’s also critical to remember, though it does sting to be reminded of this, that it takes a rate of growth higher than that of a decline to recover from the decline. Because that’s word soup, let me quickly put it in numbers. If you have $100k portfolio value and there’s a year with a 10% decrease in market value, it’ll take more than 10% growth to get the value back to $100k. In the year starting after the 10% decline, your portfolio value is $90k. In the following year, 10% of growth will only get you back to $99k. It actually takes approximately 11.1% of growth to get back to $100k. If you look at the growth of the S&P 500 for the last 30 years, you’ll see numerous years with rates of growth much higher than the overall rate of return for the period, which is due in part to the need to offset the few down years.

The purpose of this post is not, however, to remind you to ride out the down years or even just to remind you that there are going to be down years as you invest toward FIRE. Rather, this post is to counter the headlines you’re probably seeing every time you read the news or a stock app (one of the worst offenders in my humble opinion). You know the ones: “How to prepare for recession,” “Keeping investments safe in a down market,” “Adjusting your portfolio for higher inflation,” “Investments for a bear market.”

They’re catchy headlines, no doubt, made even more tempting to read by the fact that you’re seeing nothing but red for days and wondering whether there’s anything you should be doing. And I think you can guess my approach: there’s really nothing you should be doing other than waiting. Selling off stocks to head off further losses is risky business, as you might incur capital gains and it’s nearly impossible to know when the market might start heading back up.

If you do ever read any of those articles, you’ll likely find them to be…let’s say…trite, which is to say that they don’t really give you any information that’s actually useful. They’ll say things like buy bonds, keep more money in cash, and buy dividend stocks. Every so often, one might mention that there are low-volatility mutual funds available, which, for these publications, is actually pretty deep advice.

But, this underscores the point that none of these “tips” will actually help you in the long-run; at best, they’ll take some volatility out of your portfolio. As we know, however, investing in bonds or keeping your money in cash, while clearly more stable from a purely nominal perspective, will lose you money in the long-run due to the opportunity cost of not investing in equities.

So how do you keep cool in a fiery market? Well, the answer is probably as follows: nothing, subject to the below. I bet you didn’t see that coming.

There are some things you can do in a down market to take advantage of declines in the value of your assets. Chief among them is tax-loss harvesting. If you’ve got some losers, you can sell those off and re-allocate them into something else – just be aware of the wash rule discussed in the post about loss harvesting. The benefit to doing this in a down market is you might be able to reap the advantages of having some tax losses to offset some of the phantom gains and dividends you might have from other holdings.

When the market goes down, I like to scroll through my portfolio and see if there’s anything that’s taking a loss or close to taking a loss that has minimal capital gains and assess if there’s a better investment available. When I first started investing toward FIRE, I put money in a variety of ETFs and mutual funds specific to certain sectors. Over time, I became of the opinion that index tracking ETFs are the way to go long-term, so I’m slowly working on re-allocating my portfolio to hold more of them. I don’t want to sell off assets I know longer like all at once because that would mean capital gains taxes, so doing this in a down market by selling the sluggish funds helps offset some of the tax.

The other question you might have is whether to keep investing while the market is in a downturn, and the answer to this – in my opinion – is a resounding yes. This is the theory of “dollar-cost-averaging,” where you invest regardless of share price. Dollar cost averaging is essentially the opposite of timing the market because your investments come at a fixed interval rather than trying to time your buys when the price is low.

If you follow this theory, there will be times when you buy higher and there will also be times when you buy lower – such as when there’s a dip. Over time, if you keep investing, the market will move up as a whole and you’ll reap the gains. Investing in a 401(k) is effectively dollar cost averaging because you contribute a fixed amount on pre-specified intervals with each paycheck you receive.

Whether you accomplish pure dollar cost averaging or not, investing in a down market remains a solid way to reap some upside (later). That’s not to say that it doesn’t add to the anguish of watching your market value go down while it does. It’s painful to invest money, watch the market decline, and think you did something wrong or that you “lost” money. This is the same timing the market fallacy – what were you going to do, wait until the low point? How would you know when that’s coming?

Let’s do a quick example that shows how investing in a down market can bring some benefit. Say you have an account with a market value of $500k, comprised entirely of shares of XYZ. In January, you have 10,000 shares, each worth $50. Then the market starts to fall and in March those shares are worth $35, bringing your market value down to $350,000. When the price is $35, you buy 1,000 more shares for a price of $35,000, bringing the market value of your 11,000 shares to $385,000.

The market continues to fall and in June, XYZ is going for $20 per share, leaving the value of your 11,000 shares at $220,000. Hurts right? But as time goes on, the market and XYZ recover and eventually XYZ gets back to $50 per share. Now your 11,000 shares are worth $550,000, higher than you started, and in fact you have a gain of $15,000 on the 1,000 shares you bought in March. So even though you purchased in a down market, when the stock eventually got back to where it was, you’re better off because you took advantage of a price discount. You had to ride the rollercoaster to get there, but you did – it just took time. If XYZ hadn’t gone down to $35 and you wanted to buy another 1,000 shares, you may have bought them at $50 per share. If XYZ just stayed at $50, you wouldn’t have had any extra gain.

One caveat that I’ll mention about this scenario is that it applies to the market as a whole. There’s of course no guarantee that the market will actually recover, but history has shown us that it’s very likely, as time and time again, the market recovers and goes up. However, the same is not true of individual stocks, which are far more susceptible to moving independently of the market as a whole. This is why, as I mentioned above, I invest in index-tracking ETFs as much as I can, especially when loss harvesting frees up some cash to re-invest.

The post will end like so many of my others. FIRE, for the most part, is a long-term investment strategy for retirement. Although FIRE investors may take on greater risk to increase their gains over a shorter term than a traditional retirement investor, the same principles generally apply. Market swings will happen and weathering them is just as critical. However, getting through the storm can mean little more than doing absolutely nothing – or maybe even taking advantage of a dip in prices to invest more during a bargain. But there’s no need for any type of flight to safety when the market declines – pulling money out of the market runs the chance of missing upswings, which is the biggest risk of all.