Now we’re getting to the fun part – a whole post on taxes! But first, you guessed it, another disclaimer. The below is just a general overview. Taxes differ for everyone, so please consider your individual situation, and if you need help, speak with a competent professional. As stated in IRS Circular 230 (quite a read: https://www.irs.gov/tax-professionals/circular-230-tax-professionals), the below advice won’t help you get out of any penalties with the IRS, so don’t try to use it for that, because it’ll fail. Big time. The only advice that you can absolutely rely on is this: don’t mess with the IRS.

In other posts, I gave a brief explanation of some of the tax considerations of holding certain types of investments: stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and ETFs. Even with a law degree, and even having studied taxation, and even having done my taxes on my own my entire life, I’ll readily admit that it’s impossible to gain a comprehensive understanding of taxation. There are exceptions to exceptions on exceptions, all of which embodied in the prose of a lunatic manifesto so dense that the printing presses need caffeine to finish. Ok, that analogy might be a bit too much, but you get the point. Let’s just say that accountants make lots of money doing nothing more than entering numbers into software solely because of how daunting the notion of taxes can be.

On the topic of taxes you might encounter in the course of investing in pursuit of early retirement, there’s some good news and some bad news. Start with the bad: even your casual long-term FIRE investing in simple equities like stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and ETFs adds another layer of complexity to your yearly tax mess. But, there’s good news too. If you hold investments with any of the major online brokerage firms, the statements they send you will have done most of the work for you and all you need to do is enter the information they provide into tax return software (or give it to your accountant). You don’t need to start calculating how much short-term or long-term capital gain you have, or whether your dividends are qualified or not. It’ll all be on the forms ready for you.

But – you still play a role in determining certain tax treatment, including which shares to sell of a particular asset, as this directly affects how much in capital gains tax you’ll pay. I’ll talk about this more below, but for the most part, if you invest long-term you won’t have to worry about this until down the road, because you likely won’t be doing much buying and selling until you need cash for expenses.

Let’s get into it then. Below we’ll talk about taxes you’ll have to watch out for while you’re investing, followed by a discussion of tax basics you need to know when you do buy and sell shares of stock. For an overview of asset types and the basics of their taxation, I suggest you read the following post on stock and bonds, mutual funds, and ETFs.

Taxes that Sneak Up On You

It’s important to remember that there are taxes you have to watch out for while you’re saving toward your FIRE retirement or early retirement, or retirement generally. What I’m talking about are the taxes that sneak up on you without you realizing – stock dividends, bond interest payments, mutual funds gains and dividends, and ETF dividends. Regardless of the source, these are the taxes for which you become liable even though you didn’t actually engage in a buy or sell transaction; rather, they appear because you’re the owner of the particular asset. And you have to be prepared to pay them.

Mutual fund capital gains can be the most difficult since they don’t actually generate any cash at the time you incur them. Nor, if you’re doing it right, should you be getting any cash from dividends received since to maximize long-term gain hopefully you’re automatically reinvesting those dividends in additional shares of the asset.

Given that investing can lead to taxes even when you’re not actively trading, the most important thing to watch out for is that you pay enough taxes over the year. When you receive a paycheck from your employer, taxes are already withheld, so there’s not much to think about. But when you get a dividend payment from a stock share, it’s not typical for an amount to be withheld. This is especially true of capital gains distributions from mutual funds – because you won’t get any cash at all, there’s no possibility of automatic withholding.

Remember that if you end up not paying enough taxes over the year, you may be subject to – sometimes hefty – underpayment penalties. You can avoid this by keeping an eye on your dividends/capital gains and either making interim payments to the IRS or by withholding an additional amount from your paycheck to cover the additional taxes you’ll incur from investing. If you work for yourself or for some other reason are making quarterly tax payments to the IRS, then remember to account for the investment-related taxes in your quarterly payments. One of the worst things you can do to yourself (tax-wise) is to have to make a large additional tax payment when you file your return, meaning you pay all your additional taxes at once, and, in some cases with the added pain of a penalty.

But, you have no excuse not to keep on top of the taxes you might face over the year. Most online brokerage accounts give you the ability to view the taxes incurred to date at any time. You should be able to access a “tax-information” tab or page or something similar that will show you the amount of capital gains distributions, interest payments, and dividends (including whether they are qualified or not) at any point during the year. If you remember to keep tabs on these and make additional tax payments as needed, you won’t have to worry about underpaying your taxes.

One final thing to keep in mind is that mutual funds often engage in capital gains distributions toward the end of each year, so if you hold mutual fund interests, make you sure watch the distributions as the year creeps to a close and make any necessary adjustments to your taxes.

Common Investment-Related Taxes

Now that you’re on notice of taxes that can pop up, let’s talk a little more about the fundamentals of taxes related to investing. In particular, let’s talk about taxes that you incur when you choose to sell an asset. At some point, you’ll end up making a sale, whether it’s because you’ve finally retired and now need the cash, or because you want to adjust your holdings.

Even if you’re not an investment expert, the one concept you’ve probably heard of is a “capital” gain or loss, which is a gain or loss on a “capital” asset. And if you’ve never heard of this before, don’t worry, because now you have.

What’s a capital asset? One that you buy and hold only for the purpose of investment: a share of stock, a bond, a house that’s not your primary residence, a baseball card, a glass egg, celebrity hair clippings, and so on. Income from capital assets is to be distinguished from “ordinary” income, which is income from pretty much everything else, including your salary. Why does it matter? Because they’re taxed at different rates and qualify for different treatment of losses – so pay attention!

For the rest of this post, we’ll talk mostly about capital gains. For a discussion of capital losses, including how investors sometimes use them to their advantage, see this post: Tax Losses and Tax-Loss Harvesting.

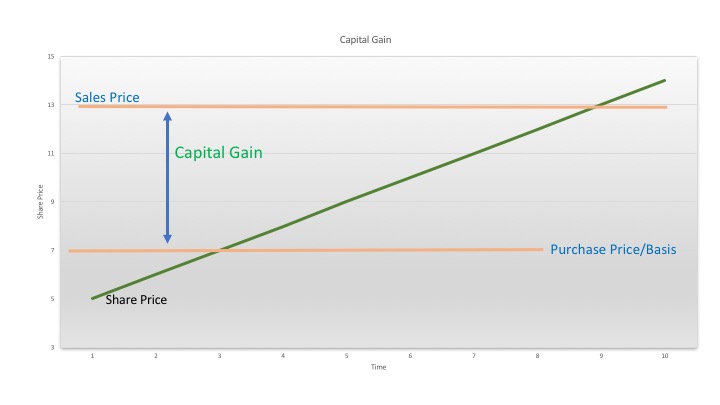

Tax Basis

Now let’s get to it. The first and most important term to remember is the word “basis.” Basis is fundamental to understanding all things tax.

Basis is the purchase price of a capital asset. If you buy a share of stock for $10, your basis in that stock is…..$10. When you sell a share of stock, your gain or loss is: Price sold minus basis. Let’s put that in big letters:

CAPITAL GAIN/LOSS = (SALES PRICE – BASIS)

Now you’ll never forget it. So selling that share for $20 will net you a capital gain of $10 ($20 – $10 = + $10), while selling that share for $6 will net you a capital loss of $4 ($6 – $10 = -$4). In the old days you had to keep track of your basis in shares, but nowadays the brokerage firms will do it for you, and if you move your account to a new firm, that information is required to transfer over, making things much easier for us. But you see how understanding basis is relevant to determining whether you’ve incurred a gain or loss on an asset. If you’re trying to figure out whether to sell a share or how much tax you might incur if you do, it’s an absolute must to know your basis in that share.

Here’s an illustrated example with different numbers:

Long-term vs. Short-Term Capital Gain/Loss

How long you hold your capital asset is relevant to whether the capital gain/loss is short-term or long-term, which, as of now, have different tax rates. Short-term means you held the capital asset for one year or less, while long-term means you held it for more than one year before you sold it. For some time now, and for the foreseeable future (though this could change), long-term capital gains are subject to a lower tax rate than short-term, incentivizing you to hold your capital assets for longer. Short-term capital gains are currently (as of writing) taxed at the same rate as ordinary income.

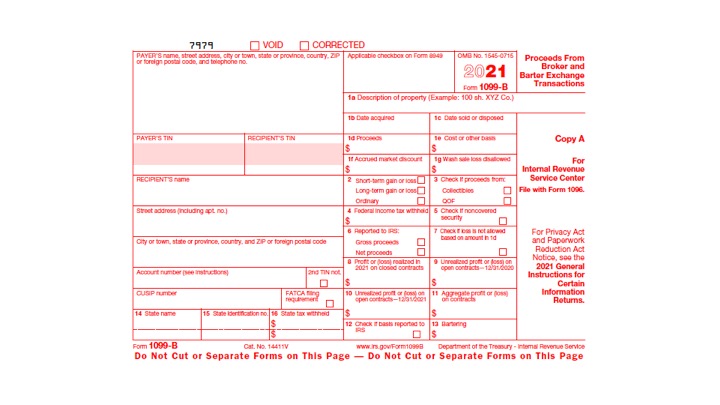

As I mentioned above, the tax forms you receive from your brokerage firm will categorize all of these nice and neatly for you, so you won’t have to worry too much about doing this yourself. Each year, they’ll send you (or more likely, you’ll download) a 1099-B and 1099-INT. If you do your own taxes, you can upload them right into your tax software. If you use an accountant (la-dee-da), print them out, sit them on your desk and use them as a coaster until coffee ring stains form, then crumple your hair and haul them loosely shuffled and hanging out of a folder to your accountant. (I’m picturing the way accountants receive information from people – it always seems disheveled and haphazard…)

Since you may be a long-term investor dutifully saving for retirement, you may not do all that much active selling of stock shares. And remember, that’s the way to do it for the long-run. Other than the taxes you can’t avoid or defer, such as capital gains coming from mutual funds and dividends and interest, you may not have all that much to think about while you’re investing to build net worth.

Tax Strategizing

What if you do want to sell some shares of stock and lock in some gains or realize some losses to deduct from your taxes? Or, what happens when you do finally make it to retirement and need to reap the benefits of all the investing you’ve been doing. Now you may have some thinking to do.

Now, what you could do – and what I’m sure quite a few people do – is open their account, find some shares they want to sell, put in a sell order, and ignore everything else. And what’ll happen is you’ll get the cash into your account from the sale and at some point in the future you’ll deal with the tax consequences. But if you do this, you may be missing out on the opportunity to minimize those taxes that you eventually face. So let’s talk about how, with a little bit of thought, you can sell your shares in a way that doesn’t cause you to incur more taxes than you need to.

The concept of minimizing your taxes on a particular sale derives from the fact that you might come to own multiple shares of the same stock at different times, meaning that you own shares of the same stock that have different holding periods (long vs. short term) and with a different basis (due to the different purchase prices).

The simplest situation for selling shares – tax wise – is when you bought all the shares of stock you wish to sell at the same time and for the same amount (meaning that you haven’t been reinvesting dividends…..). In that case, they’ll have the same basis and holding period (short or long term), meaning there’s nothing to think about, and really there’s no tax strategy related to the sale. You place a sell order and your capital gain will be what it is.

However, if you bought (or otherwise acquired) shares at different prices and at different times, then you have the opportunity to pick which of those shares to sell to minimize the tax consequences. This of course assumes that you’re not selling all of your shares of a particular stock at the same time, in which case, you just execute the sale and the gains/losses will be calculated on your 1099-B for you.

If you do have the chance to pick which shares you’re going to sell (and which shares you won’t sell), you need to know the following concepts: FIFO and LIFO, which I nearly guarantee you some accountant or tax lawyer named their dog at some point.

FIFO means First In First Out, meaning that your shares will be sold in the same order you bought them, i.e., the first ones you bought will be the first sold. LIFO is the opposite, or Last In First Out, meaning that first shares sold will be the most recent ones you bought. Generally you can set one of these methods as the default with your brokerage account or use one of these methods when executing a specific sale.

Alternatively, you can pick specific shares to sell, essentially allowing you to choose the shares with the basis and holding period of your choice. So for any given transaction, you may want to figure out what results in the lowest taxes: FIFO, LIFO, or picking specific shares.

Intuitively, it might seem that picking the shares with the highest basis might result in the lowest taxable gain. And typically that’d be right: taxes are incurred on the “gain” – meaning the difference between your sales price and your basis. However, if LIFO might result in you being subjected to a higher tax rate (say, because those shares with the highest basis would be subject to short-term capital gain), then selling shares held for longer, even though they may have a larger “gain,” may still result in lower taxes if that gain is subject to a lower rate.

How about an example of a stock sale for the numbers people. Here’s a table of our assumptions:

| Quantity | Holding Period | Basis |

| 100 | 2 years (long-term) | $10 |

| 50 | 18 months (long-term) | $15 |

| 100 | 3 months (short-term) | $20 |

Two more assumptions concerning the tax rate:

| Short-Term CG | 28% |

| Long-Term CG | 15% |

Say you want to sell 100 shares, and the current price is now $30 per share. Which ones do you sell? Let’s look first and FIFO and LIFO:

| FIFO | ||

| Sale Amount | Capital Gain | Tax |

| (100 x $30) = $3,000 | ($3,000-$1,000) = $2,000 | ($2,000 x 0.15)= $300 |

| LIFO | ||

| (100 x $30) =$3,000 | ($3,000 – $2,000) = $1,000 | ($1,000 x 0.28) = $280 |

In this case, using LIFO, your higher basis offsets the higher tax rate from selling short-term shares (held for only three months). But, there’s another way to lower taxes even further. You could sell all 50 shares held for 18 months, and then 50 from the lot held for 2 years, raising your overall basis but lowering the tax rate. Let’s see how that works out:

| Sale Amount | Capital Gain | Tax |

| (100 x $30) = $3,000 | ($3,000 – ([50x$15] + [50x$10]) = $1,750 | ($1,750 x 0.15) = $262.50 |

As you can see, there are decisions to be made. It rarely works out quite so cleanly, especially when you have fractional shares and so on, but you get the picture. The point is, if you’re looking to sell shares, and you’ve acquired those shares at different prices and at different times, you may be able to reduce your capital gains tax for the particular sale. And for the long-term investor, this isn’t all that uncommon, even if you don’t actively purchase more shares at different times. For example, if you reinvest dividends, when you go to sell you’ll have shares you acquired every time a dividend was issued.

Before you sell a share of stock, always consider whether you really want to make that sale now. Tax rates will invariably change, but one aspect that’s most likely to stay is that our tax rates will be progressive – meaning that the higher your income, the higher the tax. Ask yourself: is it really prudent to sell shares while you’re still working, or might it be worth holding them until you have a lower income and likely lower tax rates (such as when you’re retired)? How does selling a share of a particular stock fit into your long-term strategy, and are you unnecessarily incurring taxes now when you could defer them to the future? I’ll cover this in more detail in a future post.

Conclusions

Like in life generally, always consider taxes associated with your investments. They exist whether or not you’re actively buying and selling, and the consequences of ignoring them are dire. Managed properly, however, they don’t need to get in the way of your FIRE or other retirement goals.

This post was intended to introduce a few fundamental concepts about investment-related taxes, including the notion of capital vs. ordinary income, tax basis, FIFO, LIFO, and strategizing to minimize taxes. In future posts, I’ll dig more into specific tax-related situations, including ways that investors use these concepts and flexibility in the tax code to their benefit.