If you read the prior post on taxes, you may have thought – well, this all about what happens when your assets increase in value. But didn’t you say that investing has risks and that sometimes assets lose value? You’re right, I did say that, and you should never forget it. Sometimes you have to sell a share of stock at a lower price than you bought it, and sometimes, gasp!, a company goes belly-up and its shares are wiped out completely, zeroing out your asset value.

Although losses are an inevitable part of investing, this post focuses on the ways to use those losses to dampen some of the pain. Understanding how you can use tax losses, and even purposely sell some stocks when they’re down to reduce taxes, is an important aspect of FIRE, especially once you reach early retirement and are generating taxable gains as you sell shares to pay for living expenses.

Remember though that a loss is still a loss. You will lose money. All things considered, it’s better to pay tax on a gain than be able to reduce other taxes due to suffering a loss in the market. Nevertheless, the point is that sometimes we purchase shares and they just fail to thrive. Tax losses and tax-loss harvesting are taking lemons handed to you by the market and making tax-deductible lemonade.

Let’s start with the first premise: you’ve sold a share of stock at a lower market value than you purchased it, or the company in which you invested has lost all value. When this happens, the tax code allows you essentially to write-off the loss, meaning that you can deduct the amount of the loss from your taxable income, and as a result will pay less in taxes.

So, in theory, if you earn $100,000 over the year but you make one stock sale that results in a $10,000 loss, you can deduct that $10,000 loss from the income subject to taxes. Instead of paying, hypothetically, your 25% tax rate on $100,000 ($25,000 in taxes), you pay tax on $90,000 of income ($22,500 in taxes). You essentially saved $2,250 in taxes.

Now, as you probably figure, and as we’ll talk about below, it’s a little more complex than that. There are certain limitations on the types of gains you can offset with losses. And wouldn’t you believe it, the difference comes back down to the type of loss (capital vs. ordinary) and, for capital, the timing: short-term vs. long-term. So if you sell stock (or any capital asset) at a loss, you can’t just deduct it from your income outright, there are special circumstances in which you can do so.

You also see from the example above that the amount of your loss does not result in an identical reduction in taxes – meaning that you still suffer an actual loss. That is, the $10,000 stock loss does not mean you owe $10,000 less in taxes. Rather, you’re able to deduct that loss from your income, reducing the amount of taxes you pay. So the amount of your tax savings depends on your tax rate. In the example above, if your tax rate is 30%, then the value of deducting $10,000 in income is that you pay $3,000 less in taxes that year.

Ordinary Losses

First, remember the two types of income at issue for tax purposes: ordinary and capital. Capital gains and losses are gains and losses on capital assets, such as stocks, bonds, or other assets you hold for investment purposes. Ordinary income is pretty much everything else, including your salary. The major difference between the two types of income is that capital gains tend to be taxed at a lower rate than ordinary income.

In a given tax year, you can offset any ordinary income with ordinary losses. If you only receive a salary, you probably don’t have any ordinary losses. But if, for example, you hold a partnership interest or hold an interest in a business or an asset that incurs ordinary losses, you can deduct those losses from your income. The net result is your “adjusted” income, and that’s the amount on which you pay taxes. (Note that there are far more adjustments than this). If you have $100,000 of ordinary income and $50,000 in ordinary losses, your adjusted ordinary income is $50,000, and this is the amount on which you pay taxes. If your tax rate on ordinary income is 20%, then you’ll pay $10,000 in taxes for that ordinary income. ($50,000 x .20 = $10,000).

Now, what happens if your ordinary losses exceed your ordinary income? Say in year 1 you have $200,000 in ordinary losses against your $100,000 in ordinary income. For that year’s taxes, you won’t pay any tax on your ordinary income – that is, your adjusted ordinary income is $0. Then, you can carry over that additional $100,000 in losses into future years. If in year 2 you have another $150,000 in ordinary income but no ordinary losses, you can use that carried-over $100,000 loss from year 1, and your adjusted year 2 ordinary income will net to $50,000, and that’s the amount on which you’ll pay taxes.

Under current tax law, you can carry forward ordinary losses indefinitely (until they’re used up), but in the years in which you use the carryforward, you can only use it on up to 80% of your income. So, if you have $100,000 in carryforward losses and $100,000 in ordinary income, you can only use up to $80,000 of the carryforward loss in that year, and carry the remaining $20,000 into the future.

As an aside, for the casual investor saving for FIRE, or retirement generally, these types of ordinary losses are probably something you’ll never incur, or at least not in any sizeable amounts. The people who take advantage of carryforward losses tend to be fairly well-off already, and make strategic investments for the purpose of generating tax losses. When you read articles about the wealthy not paying much in taxes, this is one of the ways they do it, particularly those who own real estate. I won’t get into the mechanics, but real estate tends to generate sizable tax losses. Nevertheless, though it may not apply to the casual investor, I’m discussing these concepts here because it’s necessary background for the information below – which is relevant for FIRE investors. Trust me, I’m not writing about ordinary losses just for fun; there will be a point. Promise!

Aside over, here’s some terminology for you while we’re talking about carryforward losses. Ordinary income carryforward losses are not really called that; they’re generally referred to as Net Operating Losses, or NOLs in the lingo, and this is because they’re generally associated with business-related losses. Wage earners may incur these if, like I said above, you own an interest in a business, or if you have expenses from non-salary work. If you freelance you might have some deductible expenses, though you probably won’t have much, if any, NOLs. See my digression above.

Capital Losses

With that out the way, we can move on to the part that’s more relevant to a FIRE investor: capital gains and losses, which you’re far more likely to have as an investor due to the fact that, unfortunately, some investments just don’t go up in value.

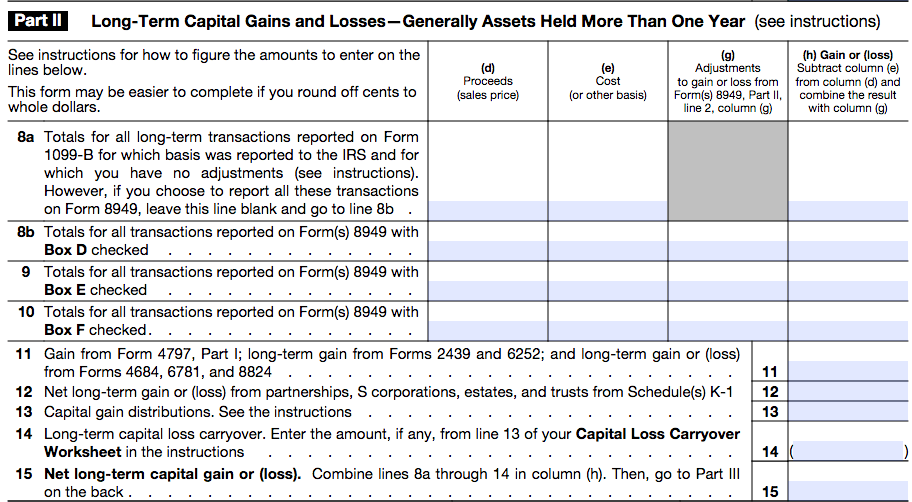

In a given year, you can deduct your capital losses from your capital gains to arrive at your net capital income for the year. So if you have $20,000 in long-term capital gains (whether from asset sales or from mutual fund distributions), and $10,000 in long-term capital losses (most likely from selling shares that are down), you’ll have $10,000 in net long-term capital gains, and that is the amount on which you’ll pay long-term capital gains tax in that year. (The same math holds true for short-term capital gains and losses).

Now, if you have a net capital loss, meaning that you have a greater capital loss than you do capital gain, you can use that capital loss to offset some of your ordinary income. I told you that information above about ordinary losses would be relevant! However, as of writing, you can only offset a maximum of $3,000 of ordinary income with capital losses in a single year. The rest of the capital losses you can carry forward to future years.

Example 1

How about an example? In year 1, you have $50,000 of ordinary income, $10,000 of capital gain, and $20,000 of capital loss. You can use that $20,000 capital loss to offset (i.e., deduct out) that $10,000 in capital gain and pay $0 capital gains tax for that year. Then you can use $3,000 of that remaining $10,000 in capital loss to offset $3,000 of your ordinary income. Your adjusted taxable ordinary income will be $47,000, and this is the only amount you’ll pay taxes on in Year 1. Then you can carry forward that $7,000 in capital loss to the following year. If you use tax software, it will likely keep track of this for you but make sure you don’t accidentally forget about tax losses you can use to offset future income.

Here’s a bit of nuance that’s relevant, by which I’m implying that not all nuance is relevant, metaphysically speaking. Stay with me on this. Offsetting capital gains with capital losses depends on whether those losses are long or short-term, and when I explain this, you’ll understand why. Your capital gains will first be offset by the same class (long or short term) of loss, and only if you have any leftover will it then offset the other type of loss. Only a series of examples can do this justice.

Example 2

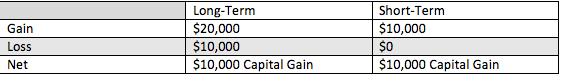

In year 1, you have $20,000 in long-term capital gain and $10,000 in short-term capital gain. Say you have $10,000 of long-term capital loss and $0 short-term capital loss. For year 1’s taxes, you can deduct the $10,000 of long-term capital loss from the $20,000 of long-term capital gain, netting you $10,000 of long-term capital gain and $10,000 of short-term capital gain that’s taxable. In this scenario, you can’t offset your short-term capital gain, which is taxed at a higher rate than your long-term capital gain, with your long-term capital loss. The IRS is not a fan of a windfall.

Example 3

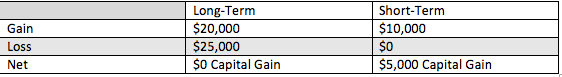

But, if instead of $10,000 in long-term capital loss, you have $25,000 in long-term capital loss, then you can first offset your $20,000 in long-term capital gain and then $5,000 of your short-term capital gain, netting you $0 in long-term capital gain and $5,000 in short-term capital gain that’s taxable for the year.

The scenario works the other way too. Instead of $25,000 of long-term capital loss, say you have $25,000 in short-term capital loss. You can first offset your $10,000 in short-term capital gain, then offset $15,000 of long-term capital gain, leaving you with $5,000 of taxable long-term capital gain for the year.

Example 4

One more? Ok! You still have $20,000 in long-term capital gain and $10,000 in short-term capital gain, but now you have $40,000 in long-term capital loss. You offset both the $20,000 in long-term capital gain and the $10,000 in short-term capital gain for $0 taxable capital gain for the year, then offset $3,000 of ordinary income. You can then carry forward $7,000 in long-term capital loss to future years.

Strategizing Losses

Trust me, there’s a reason for all these permutations, and here it is: you want to be smart when selling stocks. Unless you’re selling assets because you have to – like if you need cash or you feel like a crash is coming and you can’t overcome your instincts – you should be methodical in choosing which shares you sell (LIFO/FIFO/Individual shares), and take into account the tax implications.

For example, all things considered, short-term capital losses will help you offset more of your taxes than long-term capital losses, the reason being that short-term capital gains are taxed at a higher rate than long-term capital gains.

Take the scenario where you could end up with short-term capital losses that exceed your short-term capital gains for the year, and assume that you also have long-term capital gains in the year. Consider whether it makes sense to use those higher-value short-term capital losses against lower-taxed long-term capital gains. Maybe in that year you hold on to the stocks with accumulated long-term gains and not use up your short-term losses. Perhaps another example:

Example 5

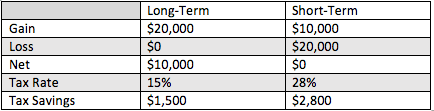

You still have $20,000 in long-term capital gain and $10,000 in short-term capital gain in the year, and are considering selling some stocks that will net you $20,000 in short-term capital losses. Your short-term capital gains rate is 28% and your long-term capital gains rate is 15%. If you sell all $20,000 of your short-term stocks at a loss, you first offset the $10,000 in short-term capital gain. By offsetting $10,000 in short-term capital gains, you save $2,800 in taxes.

But, if you then use the rest of the short-term losses to offset $10,000 of your long-term capital gain, the tax savings are not as high. You would have only paid $1,500 on that $10,000 of long-term capital gain that you offset. In effect, you’ve taken a potential offset that could be worth as much as $2,800, but only used it to offset $1,500 worth of taxes. Faced with this scenario, maybe you consider incurring only $10,000 of short-term capital loss and wait until a subsequent year for the rest (assuming you anticipate short-term capital gain).

Or maybe you hold off incurring the $20,000 of long-term capital gain (to the extent possible), and instead use that additional $10,000 short-term loss on $3,000 of ordinary income and then carry forward the rest.

Example 6: The Other Scenario

But, consider the opposite situation: you have long-term capital losses that exceed long-term capital gains, and also have short-term capital gains. It could be advantageous to use some of those long-term capital losses to offset short-term capital gains because you’ll get more value out of them. Or if you can use some long-term capital gains to offset some higher-taxed ordinary income.

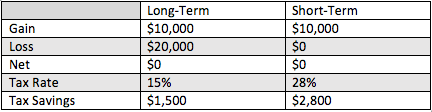

Now you have $10,000 in long-term capital gain and $10,000 in short-term capital gain in the year, and are considering selling some stocks that will net you $20,000 in long-term capital losses. In this scenario, you offset $1,500 in long-term capital gains taxes ($10,000 x 0.15) and you offset $2,800 ($10,000 x 0.28) in short-term capital gains – thereby increasing the value of the long-term capital loss.

Tax-Losses and Tax-Loss Harvesting

All told, you have to be smart about how you do this, because there are nearly endless scenarios. It might take some time to sit down and figure out what works best for you. Also consider that while you’re figuring all this out, the market is still moving. It’s not as simple as saying that you’ll wait to incur $10,000 in capital losses next year, because the shares you considered selling could go up or down in value by the time you get there, meaning you could either take a greater loss (which is always worse), or the value could go up.

It’s not an exact science. Clearly. But at some point, it’s inevitable that you’ll sell assets and incur some capital gains – otherwise, what would be the point of investing in the first place if not eventually to live off of the gains? With some effort, however, you can reduce the taxes you have to pay.

If you’re investing long-term, you might end up dealing with this on a more frequent basis than you think, especially if you engage in what’s called tax-loss harvesting. This is a method of strategically taking losses to reduce the taxes you pay on your portfolio.

Tax-loss harvesting involves evaluating what sorts of capital gains and losses you’ve accumulated over the year – whether from mutual funds passing through gains or other sales you consummated over the year – and figuring out if there are any losses you can use to offset them to lower your overall tax bill. Generally, because you can only use $3,000 of capital loss to offset ordinary income, tax-loss harvesting is not a strategy to reduce your overall taxable income, but only to lessen the burden of those sneaky taxes that you incur from long-term investing.

Tax-loss harvesting is something you might want professional help to do, unless everything above made sense to you and you can figure out the best strategy on your own. Fortunately, most online brokerage accounts will give you an option to view year-to-date tax information. You can look that over in December and see how much in short and long term capital gain you’ve incurred to date, and then compare that against any declines in asset values that would be short or long term gains in your portfolio. Additionally, and this is really helpful, most brokerage accounts will tell you the exact duration of your holding and the basis of those shares so that it’s easy to tally up how much available short or long term loss you might have.

Wash Sale

Here’s one more thing to keep in mind. If you decide to go through with tax loss harvesting, you’ll have to execute a sale sufficient to generate the losses you need. But, once you execute the sale, you’ll have the proceeds in cash from that sale, and, if you don’t actually need that money, you don’t want it to sit idly as cash. Ideally you’ll re-invest it.

One thing to be aware of when you tax-loss harvest is a “wash-sale.” A wash-sale means that you sell a security to realize the capital loss but then buy it right back. You can’t do this or the IRS will negate the transaction by disallowing the loss and the amount of the disallowed loss is added back to your basis of the replacement security. You have to wait at least 31 days to repurchase the same security to avoid this.

Keep in mind that the wash-sale rule applies not only to the same security but also to a “substantially identical” security. So if you sell one share and then use the proceeds to buy a “substantially identical” security within 30 days, the wash-sale rules will disallow your tax loss.

To add a layer of complexity (why not?), the wash-sale rules won’t apply to a “similar” security. What’s the difference between a substantially identical security and a similar one? Can’t say with certainty – that’s a legal question for a court. If you sell one ETF that tracks the Dow and then purchase a different ETF but that also tracks the Dow, that might be substantially identical. But if you purchase a new ETF that tracks the NASDAQ, that might be just similar. If you sell Boeing stock and buy Airbus, that’s most likely just similar, but if you sell Boeing Class A and purchase Boeing Class B, well, you get the idea. That’s why it might pay to talk to a real professional when doing this, because they might have a better idea (or guess).

Conclusion

Once again, remember through all of this that the tax losses discussed above mean you’ve incurred an actual loss of value. Taking advantage of the tax loss is one way to soften the blow. If you invest long-term, hopefully your losses, if any, will smooth out with the long-term upward trend of the market. But the point of this post is to say that when you do have losses, all is not actually, um, lost.